Here’s a fun mental exercise. Next time you’re making the commute to campus or taking a shortcut on one of the many farm-to-market roads scattered throughout the metroplex, take a moment to imagine your route without any of the modern features you take for granted. Remove the cars from the road. Remove the road. Wipe the signs and roadside businesses from the corners of your vision. Try to picture what this area looked like before.

It’s a small thing, that appreciation, but it’s worth the few minutes to remember what Texas was to the people who called this land home before European colonization. Especially this November, officially designated National Native American Heritage Month. In that spirit of rediscovery, we decided to round up a few resources from UNT Libraries about the rich indigenous cultures of Texas.

Caddo: The Namesake

The Caddo were an agricultural society that called the Piney Woods of East Texas home, and their territory stretched out into Oklahoma, Arkansas, and Louisiana. The Caddo relied heavily on the abundant forest wood to build their sturdy huts, canoes, and bows.

Their position in East Texas made their downfall a complicated one, as documented in The Caddo Indians: Tribes at the Convergence of Empires. Various European nations made contact with the Caddo around the same time – Spain first, in a bloody clash with the Hernando de Soto Expedition. As explorers and settlers from France, England, and the United States followed over the next century, the sophisticated Caddo tribes negotiated peace treaties with each European nation they came in contact with.

Their amenable nature toward the white European colonists kept them out of the crosshairs of American removal campaigns for a while; various Caddo tribes agreed to resettlement treaties leading up to the Texas Revolution in the 1830s. Anglo-American settlers in the region used táysha (the Caddoan word for “friend”) to name their new country: The Republic of Texas.

Lipan Apache: West Texas Warriors

The Apache people is still one of the most significant Native American cultures in the United States. Over 111,000 Apache peoples exist today, a reminder of just how vast and culturally diverse the Apache world was at its peak. Apache ancestors are thought to have migrated from Canada, and two Apache tribes eventually matriculated to the Texas area. While the Mescaleros moved to New Mexico, the Lipan Apaches held sway over West Texas. (The Apaches: Eagles of the Southwest tries to weave the sprawling Apache history into one book.)

While Apache people are remembered for their skill on horseback and fierce defense of their homelands in wars with the United States, UNT Libraries offers a few fascinating books about Apache culture.

- Apache Women Warriors by Kimberly Moore Buchanon

- Women in Apache society were asked to serve in many different roles, setting them apart from European and American women of the day. They fought in battles, served as religious mentors and were far less passive than pop culture might have you believe.

- Apache Mothers and Daughters: Four Generations of a Family by

Ruth McDonald Boyer and Narcissus Duffy Gayton

- Along the same lines, this book follows one Apache family for 35 years to show “the key roles women play in tribal life” and “the strength and the stamina of Apache women.”

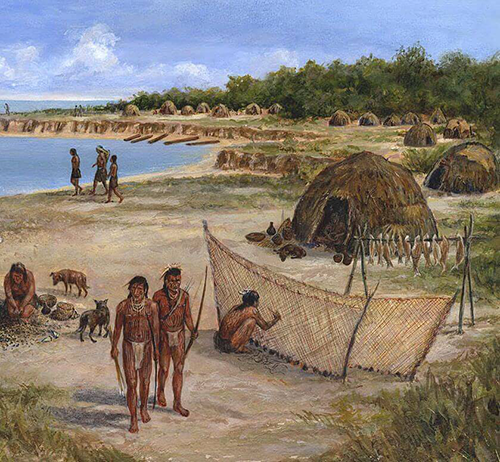

Karankawa: Lords of the Coast

Ask Spanish explorer Álvar Núñez Cabeza de Vaca, one of four survivors of the doomed Narváez expedition in 1527, and he’ll tell you the Karankawa were a peaceable sort. Nevertheless, harmful myths have evolved about the Karankawa over the centuries, no doubt because the Europeans who wrote about them coveted their coastal lands.

But de Vaca, the first European to make contact with a Texas Native American culture, was not only nursed back to health by the Karankawa but allowed to live among them as a trader for seven years. French explorers later also reported the Karankawa were a friendly people adaptable to the unpredictable coastal weather and particularly adept at facilitating trade among both native tribes and new Europeans.

Instead, it seems it was Texan colonists that spurred the Karankawa into the sort of violence they are known for today. Moses Austin, the father of Stephen F. Austin, tried to settle 300 families in the Galveston area in 1821. The Karankawa resisted the settlement of their lands, and the two groups fought violently for the next decade until Stephen F. Austin drove the Karankawa from their homelands. The Karankawa essentially died out by 1858, ending the reign of one of Texas’ most potent and influential early native peoples. You can read more about these important early Texans here.

Jumano: The First Traders

Haven’t heard of the Jumano people before? Many haven’t. Spanish explorers in the 16th century recorded meetings with them, but their expansive travel network kept anthropologists from pinning them down for centuries.

Then came University of Texas anthropologist Nancy Hickerson and her 1994 book, The Jumanos: Hunters and Traders of the South Plains. Billed as the first full-length study of the elusive Jumano society, the book explains the crucial role the Jumano played as traders and political movers-and-shakers along what would become the Rio Grande border between Texas and Mexico, stretching as far east as Caddo territory. Hickerson’s book argues the Jumano became mercenaries and spies for the Spanish before disease reduced their numbers and their influence by the 1750s. Her book fills in gaps not only in the history of South Texas but the trade interplay between native tribes in the South Plains. The Jumanos may not be the enigma they once were, as their importance to Texas is just beginning to be unearthed.

Wichita, Tawakoni and Waco: People of Gold

Someone once convinced a Spanish explorer named Francisco Coronado that he had seen one of the fabled Seven Cities of Gold in a place that would become the American southwest. Following his claim was a mistake that led to the European discovery of the Wichita people in Kansas on one of the most fruitless and consequential Spanish explorations in history.

In 1541, Coronado’s expedition had reached and razed Cibola, a pueblo town in New Mexico they incorrectly thought was one of the fabled Seven Cities of Gold. Undeterred, Coronado followed a tip from a Native American slave named The Turk that the real city of gold (named Quivira) lay elsewhere. He eventually reached Quivira near present-day Dodge City, Kansas. There he encountered the tall Wichita people, likely one of the numerous tribes dotting the plains that spoke the same language. The only gold was the sunlight glinting off their large, dome-shaped straw huts in a scattered pattern that indicated a people unaccustomed to threats.

That changed after European contact and the encroachment of the Apache from the south and Osage from the east. By the 1700s, these factors had pushed the various Wichita peoples out of their homelands, and some settled as far south as the North Texas area, where two Wichita tribes lived: the Tawakoni and the Waco.

The Wichita were not a nomadic people until contact with Europeans, and F. Todd Smith’s book illustrates how the Wichita, so separated from one another and their ancestral lands, struggled for survival in new lands during the 18th and 19th centuries in the area many UNT students call home today.

Comanche: A Proud Texas People

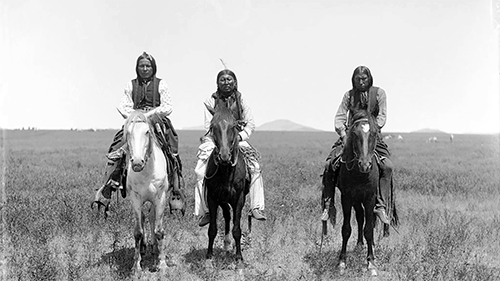

The Comanche carved out a unique place in the history of North America’s native people due to their bands’ vigorous warfare, nomadic lifestyle and the important role of “The Comanche Code-Talkers” during World War II. A few of the five major bands of Comanche ruled swaths of Texas, including the Penateka (Central Texas), Quahadis (Panhandle) and the Nokoni, Tanima and Tenawa (Cross Timbers region, including Denton).

The Comanche were defined by horses and democracy, the former giving them mobility to hunt and fight well and the latter providing Comanche society with an individual freedom that clashed with the invasive and divergent European cultures. It took almost 200 years for various countries – first Spain, then Mexico and the Republic of Texas, and finally the United States) to remove “the Lords of the Southern Plains” from their vast territory, a series of conflicts known as The Comanche Wars.

It’s no wonder a people with such a prominent role in American history has over 80 resources available through UNT Libraries. Here are just a few that stand out:

- The Comanche Empire by Pekka Hämäläinen

- The author of this book set out to challenge the assumption Native Americans were passive victims of European expansion. Instead, The Comanche Empire traces the Comanche’s path to power and the fierce resistance they put up to save their empire.

-

Myth, Memory, and Massacre: The Pease River Capture of Cynthia Ann Parker by Paul H. Carlson and Tom Crum

- Cynthia Ann Parker was only 10 years old when her family was murdered by Comanche in 1836. Taken captive, she lived as a Comanche for the next 24 years, fully embracing her new life. This book recounts her recapture and reassimilation into settler society in 1860 by Texas Rangers: “The reports of these events had implications far and near … for Parker, they separated her permanently and fatally from her Comanche husband and two of her children; for Texas, they became the stuff of history and legend.”

-

Empire of the Summer Moon: Quanah Parker and the Rise and Fall of the Comanches, the Most Powerful Indian Tribe in American History by S.C. Gwynne

- Cynthia’s son, Quanah Parker, became the last chief of the Comanche during the Red River War, the military campaign by the United States to remove Native American tribes from the Southern Plains. When Quanah Parker surrendered at Fort Sill in Oklahoma, it marked the end of Native American’s free life on the plains.