Page Contents 11 minute read.

Introduction

If you are thinking about scanning your own objects for inclusion in The Portal to Texas History or the UNT Digital Library, there are a number of considerations. In order to efficiently create the highest-quality scans of your materials, we have compiled this list of suggestions about how to scan objects so that they will meet our minimum requirements.

Folder Management and File Naming

One of the biggest issues with digitization is the organization and management of objects you have created for current and past projects. It greatly helps to think this problem through before beginning a project as it can come back and cause problems at a later date.

1 Digital Object = 1 Folder

In the Digital Projects Unit, each digital object gets its own folder in which to store the files. For example:

- A photographic print will have 2 digital images in a folder: 1 image of the front and 1 image of the back.

- A book will have a single folder containing the images for every page.

Naming Object Folders and Files

When naming scanned files, use the unique identifier of the item as the folder name as well as the individual file names (for more information about creating identifiers, see About Unique Identifiers). Using the identifiers as the folder and file names makes it easier to sort the digital objects and to match them up with the physical counterparts if you need to compare scans to the original. Since files cannot be named with non-alphanumeric/special characters, only use combinations of the following characters:

- A-Z

- a-z

- 0-9

- hyphens (-)

We also use underscores (_) in file names to distinguish between the original identifier and information added during scanning. For example, if there is more than one digital image then each digital image will need a suffix to distinguish it. Each view of the object should have a number appended to it, in the order that you would want them to be viewable online. It is important to append numbers so that the files will automatically fall in order; if you use something like “front” and “back” the computer will sort the files incorrectly (back would come first alphabetically).

Example

If the accession number for a photograph is 1919-Tomahawk-1, when you scan the image you will have the following file names:

- Folder: 1919-Tomahawk-1

- Image 1 (front): 1919-Tomahawk-1_01.tif

- Image 2 (back): 1919-Tomahawk-1_02.tif

Other tips for file-naming:

- Do not add a number suffix if there is only one scan, such as when scanning negatives. This way you know there was only one image whereas if you add a _01 suffix to a single image, three years later someone may wonder where _02 is.

- When numbering a series of files always “pad” the number with zeroes in front or they will not show up in order when you open the folder. If you have 1-9999 items, add three zeroes (e.g., 0001, 0010, etc.)

- Include the three-letter extension for file types (e.g., tif)

For more guidelines and examples of how to structure images in folders, see Organizing Files.

Standards

What is Resolution?

Resolution refers to the density of pixels in an image and is a measurement of height by width at a certain pixel density (ppi). Digital images have no real absolute size or pixel density, only a certain number of pixels in each dimension.

ppi? dpi?

These terms are incorrectly used interchangeably but refer to two entirely different measurements.

- PPI = pixels per inch (PPI is used when the image is still in the computer as you are measuring pixel density.)

- DPI = dots per inch (DPI is used when speaking about physical prints as you are talking about an actual number of dots of ink per inch.)

The most important factor with resolution is that you need to have a high enough pixel density (ppi) for the images you scan to meet your needs. You can always “res” an image down to a lower ppi at the same size, but you can never increase the resolution after the original scan has been made.

Example

One way to think about this is akin to the creation of a mosaic. If you are making a 4’ by 4’ mosaic and you use 1’ tiles then your mosaic won’t look as much like an image as just 16 big blocks of color. If you use 1” tiles you now have 192 blocks from which to make a picture, and a much better image is created.

The image below exemplifies how this affects the way a digital image looks. The left side is the equivalent of the 4’ by 4’ mosaic using 1’ tiles (i.e. 400 pixels x 400 pixels at 8ppi) where a vague idea of the picture is formed, but nothing concrete. The right side is the digital equivalent of using the 1” tiles (i.e. 12x the resolution, so 400 pixels x 400 pixels at 96 ppi).

UNT Libraries’ Standards

The Digital Projects Lab at the UNT Libraries has developed a simple set of scanning specifications that it uses throughout all of the digital projects carried out in the Lab. The standards were created to provide the highest-quality reproductions while keeping in mind the cost of storing the digital copy. Many national and international standards were consulted when creating these standards, and we feel that they stand up well as a basic set of scanning standards.

Scanning

What Makes a Good Scan

Before diving into the nitty-gritty of scanner drivers and Photoshop adjustments, it helps to understand what makes a good scan – but how do you define a “good” scan? A scan is a digital representation of a physical object, so a good scan would be a faithful reproduction of that object without distractions.

The following examples show some of the “distractions” that affect image quality. Note: borders have been added to the images to make the margins of the scans more noticeable.

Skew (crookedness)

If your scan is crooked it looks unprofessional and it is distracting for the viewer. The image should look like this:

Cropping

This image has been cropped too closely. If you crop too tightly then you are not doing justice to the object since information is being stripped away and the image is no longer being faithfully reproduced.

This image has been cropped too loosely. If you crop an image too loosely the the file size is larger than it needs to be.

Also, if your system displays fixed-width images, then the displayed image will be smaller than it otherwise could be. For example, if your system displays images on the web at 700 pixels wide and you have a border of 10 pixels all the way around the image, then the actual image is displayed as 680 pixels wide. If the same image has a border of 75 pixels then the original image is displayed as 550 pixels wide and you lose 150 pixels to the border - that’s more than 20% of the total size!

The image should look like this:

Image Tones

This image is too dark. If the image is much darker than the original then details in the shadows are lost and the image is no longer a faithful representation.

This image is too light. If the image is much lighter than the original then details in the highlights are now lost and the image is no longer a faithful representation.

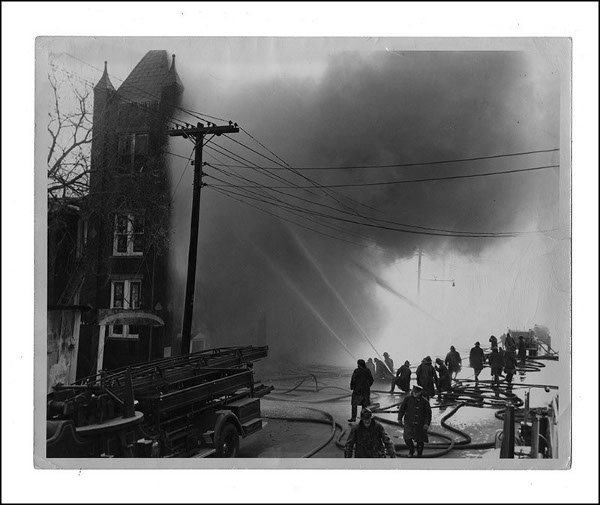

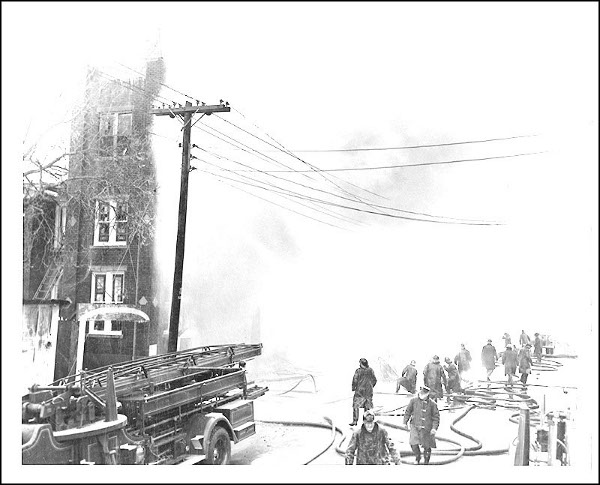

The image should look like this:

Archival Scanning

Since our intention is to preserve archival copies of physical objects, we scan the entire object, meaning that: all of the item is visible (which is why we leave a border around the outside) and all views of the item are included even if the back of a text or photo is blank. The front and back are always scanned using the same settings, including orientation and tone (i.e., if the front is grayscale then the back is scanned in grayscale). If there is text on the back of an object in a different orientation, the item can be rotated when users view it online, but it can be disorienting if the front and back are not facing the same direction when users are switching between the views.

Scanning Hardware

There are a variety of scanners available depending on your price range and the items that you have to scan. The basic hardware alone will not change your ability to scan to our specifications. We may be able to give you some recommendations, but you’ll have to make decisions about what will work for you.

For comparison, in the Digital Projects Lab we use a range of Epson flatbed scanners for the majority of our work, as they are fast, high quality, robust, and multi-functional.

The Epson Perfection V700 Photo scanner is the workhorse of our department due to the quality of its output, the low price point, and its multi-functionality. This scanner can be used to scan any reflective (prints) or transmissive (negatives, slides) material up to 8.5” x 11.7”. It also comes with holders to scan 35mm negatives and slides, medium format negatives and slides, and 4x5 negatives and slides.

Scanning Software

There are also many kinds of scanning software available. What you use will depend on what kind of scanners you choose to use. Again, we may be able to give you recommendations, but we will not be able to give you specific instructions if it is not software that we use (and are familiar with).

For comparison, we use Adobe Photoshop CS6 in the Digital Projects Unit. If you want to use Photoshop, you may qualify for Adobe’s educational pricing (check www.adobe.com for details).

We use Epson’s TWAIN driver to run the scanner through Adobe Photoshop CS6 (from now on, referred to as just “Photoshop”), so as soon as the scanner is finished scanning, the file is in Photoshop. Fun fact: TWAIN stands for Technology Without An Interesting Name.

“I’ll fix it in Photoshop”

The mentality of “I’ll fix it in Photoshop” is deceiving. There are many things that can be tweaked and corrected, but always plan on getting the best scan you can up front. If you often have to resort to Photoshop to “fix” things then your scanning workflow may need some changes.

Digital Preservation

Digital preservation is an active area of research where many major questions remain unanswered. However progress is being made on many fronts, and the community as a whole is in a much better place than we were only five years ago. Remember we had centuries to figure out how to preserve paper-based documents and well over 150 years to figure out how to take care of photographic images. Some of the technologies and techniques we are looking at today haven’t even been around for a decade.

A practical model for digital preservation has been outlined in the makeup of the Federal Depository Library Program and later, in a much easier-to-remember initiative, LOCKSS (Lots of Copies Keep Stuff Safe). The idea of having multiple copies of your master files is a sound, tested and practiced method for making sure you have your saved content in the future.

Things to Remember

- When sending any digital materials to the Digital Projects Lab, you should ALWAYS keep a back-up copy of your master files.

- If your materials do not meet our standards, we will return the images to be fixed or rescanned. (We will include a description of the problems and suggestions about how to fix them.)

- We recommend that you send your materials in smaller batches (even

after we check your first 50 scans).

- A smaller number of images (e.g., 100 images versus 1000) can be checked more quickly.

- Fewer images also means that if there are problems, we can catch them so that you have fewer things to fix.

- Make sure that you keep detailed instructions about how you scan your items to our specifications (especially if you have multiple people scanning).

- Communicating any questions or concerns that you have early-on means that we can discuss them with you before you have large numbers of images to edit.